Sophie Smyth

This week, a report by MPs discussed the lack of female participation in sport, concluding that females, across cultural and social spectra, leave sport early, if they ever really take it up at all.

Surprising? I’m afraid not. Disappointing? Very.

Among the various factors cited as reasons, the report suggests that lack of adequate facilities, uninspiring lessons and disparaging comments drive women and girls from sport more quickly than you can say, ‘football is a man’s game’.

Also this week though, I’ve been lucky enough to witness some of the world’s strongest, fastest, long- and high-jumpiest athletes compete in my home city. And, shock horror, some of them have been women. Apparently women have exactly the same capacity for competitive sporting greatness as men. Who would have guessed?

But who knows how many sporting greats the world has been missing out on because of society’s inability to engage women as sporting equals?

So here’s my incomprehensive guide to keeping women in sport – and gender out of it.

Libby Clegg and Mikail Huggins

Mind that language

The language of sport is unashamedly masculine. Well, it’s time to be ashamed.

If a girl is sporty, she’s a tomboy. If she has an athletic physique, she’s manly. And then there are the just plain rude comments on how a woman looks while running a marathon, acing a triathlon or, you know, just winning Wimbledon.

Of course, it was only the ‘women’s title’ that Marion Bartoli won; as though that’s in some way less valid than Wimbledon itself, which is, of course, the men’s version. Somehow men are always held up as the ‘norm’ in sport – the football, the rugby, the tennis, all represent the male competition – while women’s football, women’s rugby and women’s tennis always use that lovely gender prefix to explain, in case you were confused, that you aren’t watching the actual sport.

It’s not necessary, it’s endemic and, frankly, it’s offensive. Drop the man-nouns, stop with the categorisation, and, if you simply have to comment, focus on the achievements of the person, not the body parts they possess.

Change it up

Teenage years are, let’s face it, the most awkward, self-conscious of times. Add to that the pressure of unattainable magazine standards and the joy of communal changing rooms, and you’re going to find drop-off rates for P.E. gathering pace.

We’re not princesses but it’s just not easy to strip down to your soul in grotty rooms so small that air is a luxury, when your confidence is already lower than your centre of gravity. So why the hell would anyone volunteer to remove those precious last lines of defence in public, if they just don’t have to?

Privacy isn’t opulent, it’s humane. And with more room to manoeuvre and less room for embarrassment, maybe everyone can enjoy exercise without the dreaded changing room horror-show.

Picture this

Over the years, the fashion of body types has changed. It’s not wicked or shameful, it’s just fact. Whether magazine cynicism, photo-manipulation or the fashion industry in general has any case to answer is not my judgement to make, but for women, young and old, there is now a definite conflation of a healthy body and a thin one.

Dieting is everywhere, meaning that starving oneself to social acceptability is more accessible and popular than the alternative – being, yuk, a healthy weight. When skinny is sexy and muscles reviled, how can anyone expect impressionable young people to stick to sport instead of opting for the glamour of poor diet and a chronic lack of energy?

It’s not embarrassing for men to look fit and it shouldn’t be for women either. So let’s stop telling our young people that thigh gaps and bikini bridges are a metric for beauty, and start putting out healthy images of physical and mental wellbeing to which we can all aspire.

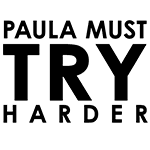

Paula.